One of the greatest mistakes we make in literary studies—and as teachers of literature—is privileging one form of literacy above all others. Namely, literacy as silent reading.

In our classrooms, we view reading aloud with disdain. Asking students to take turns reading a text aloud offends our sensibilities as literature professors. It’s remedial. Childish. Appropriate for an elementary school classroom, perhaps, but it has no place in our hallowed halls of higher learning.

How odd it is, then, that so many academic conferences in the humanities consist of nothing but rooms full of professors looking down at papers, reading them aloud. I can only imagine that this form of reading aloud is valid in our eyes while students reading aloud in our classes is not, because it is pedagogically and historically aligned with that realm of culture in which it is legitimate to read texts aloud—the realm of the sacred, the rite of the scripture, the ritual of someone we presume to be intellectually and spiritually superior exulting and professing before the masses. Which explains why we deem it acceptable for ourselves to read passages aloud in class, so long as it is done in a tremulous, dramatic voice.

Reading aloud is a right reserved for the professor.

And how wrong this is. How drearily, dreadfully, dismally wrong this is.

Sheridan Blau argues in The Literature Workshop that one of the most powerful tools at the disposal of readers is rereading. And reading aloud—reading out loud—is in turn one of the most powerful ways of rereading. It’s active, performative, and engaging, an incredibly rewarding strategy for understanding difficult texts. And it’s a technique too easily tossed aside in the undergraduate classroom—and in the graduate student classroom for that matter.

Not every professor has abandoned this seemingly elementary technique, of course; for example, my ProfHacker colleague Jason Jones has long defended the value of reading aloud. And last week in my Science Fiction course I was reminded of exactly how indispensable—and fun—reading aloud can be for students.

This course is an upper level class full of English majors. And I mean full. There are 53 students enrolled, just about double my usual size of 27 students. And yet I try to lead this class with as much discussion and participation as a graduate seminar. We’re only three weeks in, but I’m delighted so far that I’ve been able to involve so many students, and hear so many voices over the course of our 75-minute sessions.

Because my class last Thursday went particularly well, and because it highlights the value of students reading aloud, I want to walk through two activities we did. Both led to vigorous discussions that helped to illuminate some questions troubling my students about Volume I of Frankenstein, our first novel of the semester.

Reading Frankenstein Aloud

I picked the following passage to read aloud in class, because it contains some of the most telling imagery concerning Frankenstein’s loss of humanity as he attempts to create life. It’s a rich paragraph, complicating the reductive and moralistic dictum that Frankenstein was “playing God.”

From Frankenstein (1818), Chapter 3, paragraph 9:

- We began by reading the passage aloud using what Blau calls the “jump-in” method. I’ve heard other people call it popcorn-style. We simply bounce around the room, with students voluntarily jumping in to read a few sentences to the class, after which somebody else jumps in, as if taking the baton from the previous reader. The professor doesn’t interrupt or call on anybody to read; the reading is totally student generated.

- After we finished reading the passage, we took nominations for the most important sentence or phrase from the paragraph—the sentence or phrase most pivotal or rich with interpretive potential. Peter Elbow would call it “the center of gravity” of the paragraph. The students shouted out these lines, and I typed them into this Google Doc, displayed live on the projection screen in the front of the lecture hall.

- With no debate of the nominees, we voted (by hand count) for the most significant of these ten lines.

- Finally, we had a class discussion, in which supporters of each line defended their vote. We didn’t discuss every line, especially since there was one clear “winner” and two runner-ups. But even limiting our debate to three lines of the paragraph gave us three entryways into the passage, three facets which, when angled just right, revealed something new about Frankenstein—or rather, Shelley’s indictment of Frankenstein.

I’m convinced that such a productive discussion wouldn’t have occurred if the students hadn’t first reread the passage aloud. I’m likewise convinced that merely asking students to reread the passage silently before the exercise wouldn’t have yielded such rich interpretive fruits. It’s the reading aloud that does it. The vocalization for the students who did the reading, the texture of the voices for the students who listened, the attentive anticipation of everyone as they awaited the next reader to jump in from the seat next to them or from across the room.

Reading Aloud and Touching Frankenstein

We read yet another passage aloud, again jump-in fashion, afterwards. My goal this time was to pinpoint the precise moment when Victor Frankenstein goes from praising his act of creation to being repulsed by it. I was motivated by a student’s blog post, in which she had wondered why Frankenstein suddenly became horrified by his creature, when he had worked so hard to create it. To answer this question of why, we need to know when he became afraid.

So our class read aloud, popcorn style, from the first three paragraphs of Chapter 4:

After we finished reading this passage aloud—again, a fundamental kind of rereading—I asked students to point to the exact word when Frankenstein’s attitude toward his creation changes from delight to revulsion. Literally—I asked students to point with their finger to the spot on the page where this transformation occurs. They had to physically touch the page with their index finger, and leave it there, while we consider the class’s various answers.

I’ve borrowed this pointing method from Peter Elbow, who uses it in the context of teaching composition. In Elbow’s method, peer readers help their fellow writers by pointing to words that resonate with them. But pointing works just as well when reading literary works. There’s something about that tactile connection with the page that for a moment is far more meaningful to the student than anything he or she might have underlined or highlighted. And here, in this exercise, pointing forces students to make a choice, to take a stance with the text. There’s no hemming and hawing, no vague determination that the transformation in question happens somewhere on page 85 or wherever.

Of course, with Frankenstein there is no single correct answer of when his disgust takes shape. It is a contested question, minor perhaps, but yet our tentative answers, backed with literally physical evidence in the form of the finger on the page, opens up the text. Questions of tone and narrative perspective arise. Irony enters in. Even punctuation, as when a student convincingly argued that the reversal occurs in the em dash between “Beautiful!” and “Great God!”

None of these considerations would have been as easily accessible to us without, first, reading the passage, and then, rereading it. And more precisely, rereading it aloud. When students read aloud they become voices in the classroom, authorities in the classroom, empowered to speak both during the reading and even more critically, after the reading.

This course considers the storytelling potential of graphic novels, an often neglected form of artistic and narrative expression with a long and rich history. Boldly combining images and text, graphic novels of recent years have explored divisive issues often considered the domain of “serious” literature: immigration, racism, war and terrorism, dysfunctional families, and much more. Informed by literary theory and visual culture studies, we will analyze both mainstream and indie graphic novels. In particular, we will be especially attentive to the unique visual grammar of the medium, exploring graphic novels that challenge the conventions of genre, narrative, and high and low culture. While our focus will be on American graphic novelists, we will touch upon artistic traditions from across the globe. Works studied may include Nat Turner by Kyle Baker, Fun Home by Alison Bechdel, Black Hole by Charles Burns, Sand Man by Neil Gaiman, Asterios Polyp by David Mazzucchelli, Exit Wounds by Rutu Modan, Watchmen by Alan Moore, Uzumaki by Junji Ito, In My Hour of Darkness by Wilfred Santiago, Maus by Art Speigelman, and Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth by Chris Ware.

This course considers the storytelling potential of graphic novels, an often neglected form of artistic and narrative expression with a long and rich history. Boldly combining images and text, graphic novels of recent years have explored divisive issues often considered the domain of “serious” literature: immigration, racism, war and terrorism, dysfunctional families, and much more. Informed by literary theory and visual culture studies, we will analyze both mainstream and indie graphic novels. In particular, we will be especially attentive to the unique visual grammar of the medium, exploring graphic novels that challenge the conventions of genre, narrative, and high and low culture. While our focus will be on American graphic novelists, we will touch upon artistic traditions from across the globe. Works studied may include Nat Turner by Kyle Baker, Fun Home by Alison Bechdel, Black Hole by Charles Burns, Sand Man by Neil Gaiman, Asterios Polyp by David Mazzucchelli, Exit Wounds by Rutu Modan, Watchmen by Alan Moore, Uzumaki by Junji Ito, In My Hour of Darkness by Wilfred Santiago, Maus by Art Speigelman, and Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth by Chris Ware.

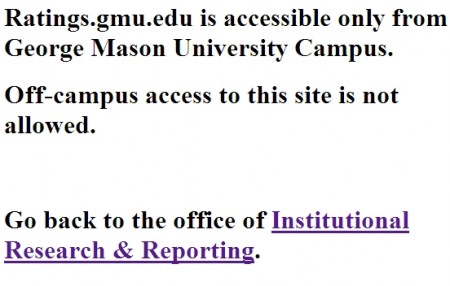

To be fair, I’m hoping that the typo has been corrected since I captured this screen shot in May. But I wouldn’t know for sure. You see, it’s August and I’m off-campus right now, as are most faculty and students, and I can’t even electronically access my own teaching evaluations, let alone those of other professors, unless I’m physically there.

To be fair, I’m hoping that the typo has been corrected since I captured this screen shot in May. But I wouldn’t know for sure. You see, it’s August and I’m off-campus right now, as are most faculty and students, and I can’t even electronically access my own teaching evaluations, let alone those of other professors, unless I’m physically there.