What follows is a comprehensive list of digital humanities sessions at the 2013 Modern Language Association Conference in Boston.

What follows is a comprehensive list of digital humanities sessions at the 2013 Modern Language Association Conference in Boston.

These are sessions that in some way address the influence and impact of digital materials and tools upon language, literary, textual, and media studies, as well as upon online pedagogy and scholarly communication. The 2013 list stands at 66 sessions, a slight increase from 58 sessions in 2012 (and 44 in 2011, and only 27 the year before). Perhaps the incremental increase this year means that the digital humanities presence at the convention is topping out, leveling out at 8% of the 795 total sessions. Or maybe it’s an indicator of growing resistance to what some see as the hegemony of digital humanities. Or it could be that I simply missed some sessions—if so, please correct me in the comments and I’ll add the session to the list.

In addition to events on the official program, there’s also a pre-convention workshop, Getting Started in the Digital Humanities with DHCommons (registration is now closed for this, alas) and a Technology and Humanities “unconference” (registration still open). And I’ll also highly recommend the Electronic Literature Exhibit, in the Exhibit Hall.

One final note: the title of each panel links back to its official description in the convention program, which occasionally includes supplemental material uploaded by panel participants.

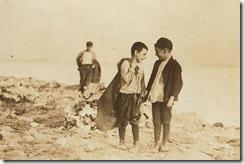

[Photo credit: Lewis Hine, Boys picking over garbage on "the Dumps," Boston, 1909 / Courtesy of the Library of Congress]

Thursday, 3 January, 8:30–11:30 a.m., Republic B, Sheraton

Presiding: Brian Croxall, Emory Univ.; Adeline Koh, Richard Stockton Coll. of New Jersey

This workshop is an "unconference" on digital pedagogy. Unconferences are participant-driven gatherings where attendees spontaneously generate the itinerary. Participants will propose discussion topics in advance on our Web site, voting on final sessions at the workshop’s start. Attendees will consider what they would like to learn and instruct others about teaching with technology. Preregistration required.

Thursday, 3 January, 8:30–11:30 a.m., Republic A, Sheraton

Presiding: Alison Byerly, Middlebury Coll.; Kathleen Fitzpatrick, MLA; Katherine A. Rowe, Bryn Mawr Coll.

Facilitated discussion about evaluating work in digital media (e.g., scholarly editions, databases, digital mapping projects, born-digital creative or scholarly work). Designed for both creators of digital materials and administrators or colleagues who evaluate those materials, the workshop will propose strategies for documenting, presenting, and evaluating such work. Preregistration required.

Thursday, 3 January, 12:00 noon–1:15 p.m., Jefferson, Sheraton

Presiding: Jude V. Nixon, Salem State Univ.

- "The Collected Works of Elizabeth Barrett Browning: Print Editions, Digital Surrounds, and Preservation," Sandra M. Donaldson, Univ. of North Dakota; Marjorie I. Stone, Dalhousie Univ.

- "A Virtual Edition of William Morris’s Collected Works," Florence S. Boos, Univ. of Iowa

- "The Novels of Sutton E. Griggs: A Critical Edition," Tess Chakkalakal, Bowdoin Coll.

- "Editing Henry James in the Digital Age," Pierre A. Walker, Salem State Univ.

22. Expanding Access: Building Bridges within Digital Humanities

Thursday, 3 January, 12:00 noon–1:15 p.m., 205, Hynes

Presiding: Trent M. Kays, Univ. of Minnesota, Twin Cities; Lee Skallerup Bessette, Morehead State Univ.

Speakers: Marc Fortin, Queen’s Univ.; Alexander Gil, Univ. of Virginia; Brian Larson, Univ. of Minnesota, Twin Cities; Sophie Marcotte, Concordia Univ.; Ernesto Priego, London, England

Digital humanities are often seen to be a monolith, as shown in recent publications that focus almost exclusively on the United States and English-language projects. This roundtable will bring together digital humanities scholars from seemingly disparate disciplines to show how bridges can be built among languages, cultures, and geographic regions in and through digital humanities.

Thursday, 3 January, 12:00 noon–1:15 p.m., The Fens, Sheraton

- "From Text to Work: Douglas Coupland’s Digital Interruptions and the Labor of Form," Paul Benzon, Temple Univ., Philadelphia

- "The Mediated Geographies of Miéville’s The City and the City," Richard Menke, Univ. of Georgia

- "Tom McCarthy’s Prehistory of Media," Aaron S. Worth, Boston Univ.

Thursday, 3 January, 1:45–3:00 p.m., 301, Hynes

Presiding: Eileen Lohka, Univ. of Calgary; Catherine Perry, Univ. of Notre Dame

- "The Internet Poetics of Patrick Chamoiseau and Édouard Glissant," Roxanna Curto, Univ. of Iowa

- "Toussaint en Amérique: Collaborations, dialogues et créations multi-disciplinaires," Alain-Philippe Durand, Univ. of Arizona

- "Bandes dessinées téléchargeables: Un nouveau moyen de mesurer la diffusion de la langue française au 21ème siècle," Henri-Simon Blanc-Hoang, Defense Lang. Inst.

Thursday, 3 January, 1:45–3:00 p.m., 206, Hynes

Presiding: Sébastien Dubreil, Univ. of Tennessee, Knoxville

- "Teaching Language and Culture through Social Media and Networks," Edward M. Dixon, Univ. of Pennsylvania

- "Developing Pronunciation Skills at the Introductory Level: Motivating Students through Interpersonal Audio Discussions," Cindy Lepore, Univ. of Alabama, Tuscaloosa

- "Español Two Hundred: Bridging Medium, Collaboration, and Communities of Practice," Adolfo Carrillo Cabello, Iowa State Univ.; Cristina Pardo Ballester, Iowa State Univ.

Thursday, 3 January, 1:45–3:00 p.m., Public Garden, Sheraton

Presiding: Nate Kreuter, Western Carolina Univ.

- "Metathesiophobia and the Impossible Math of the Scholarly Monograph," Patricia Roberts-Miller, Univ. of Texas, Austin

- "Hope and Habit(u)s?" Victor J. Vitanza, Clemson Univ.

- "Publishing Long-Form Multimedia Scholarship: Thinking about Bookness," Gail E. Hawisher, Univ. of Illinois, Urbana; Cynthia L. Selfe, Ohio State Univ., Columbus

Thursday, 3 January, 3:30–4:45 p.m., Hampton, Sheraton

Presiding: Cynthia R. Port, Coastal Carolina Univ.

- "Aging as Obsolescence: Remediating Old Narratives in a New Age," Erin Lamb, Hiram Coll.

- "Typewriters to Tweeters: Women, Aging, and Technological Literacy," Lauren Marshall Bowen, Michigan Technological Univ.

- "The New Obsolescence of New Media: Political Affect and Retrotechnologies," Jen Boyle, Coastal Carolina Univ.

Thursday, 3 January, 3:30–4:45 p.m., Public Garden, Sheraton

Presiding: Shelley Fisher Fishkin, Stanford Univ.

- "Living Word," Corrie Claiborne, Morehouse Coll.

- "Digital Griots," Adam Banks, Univ. of Kentucky

- "Hip-Hop Archives," Marcyliena Morgan, Harvard Univ.

Thursday, 3 January, 5:15–6:30 p.m., Berkeley, Sheraton

Presiding: Robert R. Bleil, Coll. of Coastal Georgia; Jennifer Gray, Coll. of Coastal Georgia

Speakers: Susan Cook, Southern New Hampshire Univ.; Christopher Dickman, Saint Louis Univ.; T. Geiger, Syracuse Univ.; Jennifer Gray; Matthew Parfitt, Boston Univ.; James Sanchez, Texas Christian Univ.

Responding: Robert R. Bleil

Nicholas Carr’s 2008 article "Is Google Making Us Stupid?" and his 2010 book The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains argue that the paradigms of our digital lives have shifted significantly in two decades of living life online. This roundtable unites teachers of composition and literature to explore cultural, psychological, and developmental changes for students and teachers.

Thursday, 3 January, 5:15–6:30 p.m., Fairfax B, Sheraton

Presiding: Tim Cassedy, Southern Methodist Univ.

Speakers: Robin Bernstein, Harvard Univ.; Lindsay DiCuirci, Univ. of Maryland Baltimore County; Laura Fisher, New York Univ.; Laurie Lambert, New York Univ.; Janice A. Radway, Northwestern Univ.; Joseph Rezek, Boston Univ.

Archivally driven research is changing the methodologies with which we approach the past, the types of questions that we can ask and answer, and the historical voices that are heard and suppressed. The session will address the role of archives, both digital and material, in literary and cultural studies. What risks and rewards do we need to be aware of when we use them?

Thursday, 3 January, 5:15–6:30 p.m., The Fens, Sheraton

Presiding: Lori A. Emerson, Univ. of Colorado, Boulder

- "Apple Macintosh and the Ideology of the User-Friendly," Lori A. Emerson

- "OCR (Optical Character Recognition) and the Vestigial Aesthetics of Machine Vision," Zach Whalen, Univ. of Mary Washington

- "Lost in Plain Sight: Microdot Technology and the Compression of Reading," Paul Benzon, Temple Univ., Philadelphia

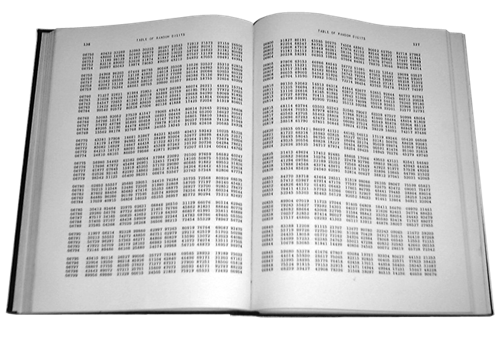

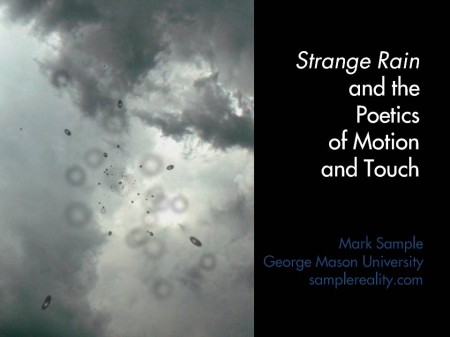

- "An Account of Randomness in Literary Computing," Mark Sample, George Mason Univ.

Thursday, 3 January, 5:15–6:30 p.m., Beacon F, Sheraton

Presiding: Greg Barnhisel, Duquesne Univ.

- "Printing the Third Dimension in the Renaissance," Travis D. Williams, Univ. of Rhode Island

- "Mediating Power in American Editions of Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea," Matthew Lavin, Univ. of Iowa

- "Printed Books, Digital Poetics, and the Aesthetic of Bookishness," Jessica Pressman, Yale Univ.

Responding: Stephanie Ann Smith, Univ. of Florida

Thursday, 3 January, 5:15–6:30 p.m., Liberty C, Sheraton

Presiding: Andrew Piper, McGill Univ.

Speakers: Mark Algee-Hewitt, Stanford Univ.; Lindsey Eckert, Univ. of Toronto; Neil Fraistat, Univ. of Maryland, College Park; Matthew Jockers, Univ. of Nebraska, Lincoln; Laura C. Mandell, Texas A&M Univ., College Station; Jeffrey Thompson Schnapp, Harvard Univ.

As part of the ongoing debate about the impact and efficacy of the digital humanities, this roundtable will explore the theoretical, practical, and political implications of the rise of the literary lab. How will changes in the materiality and spatiality of our research and writing change the nature of that research? How will the literary lab impact the way we work?

Thursday, 3 January, 7:00–8:15 p.m., Gardner, Sheraton

- "Occupy Theory: Tahrir and Global Occupy Two Years After," Nicholas Mirzoeff, New York Univ.

- "Tweeting the Revolution: Activism, Risk, and Mediated Copresence," Beth M. Coleman, Univ. of Waterloo

Thursday, 3 January, 7:00–8:15 p.m., Hampton, Sheraton

Speakers: Douglas M. Armato, Univ. of Minnesota Press; Jamie Skye Bianco, Univ. of Pittsburgh; Matthew K. Gold, New York City Coll. of Tech., City Univ. of New York; Jennifer Laherty, Indiana Univ., Bloomington; Monica McCormick, New York Univ.; Katie Rawson, Emory Univ.

As open-access scholarly publishing matures and movements such as the Elsevier boycott continue to grow, open-access publications have begun to move beyond the simple (but crucial) principle of openness toward an ideal of interactivity. This session will explore innovative examples of open-access scholarly publishing that showcase new types of social, interactive, mixed-media texts.

167. Digital Humanities and Theory

Thursday, 3 January, 7:00–8:15 p.m., Riverway, Sheraton

Presiding: Stefano Franchi, Texas A&M Univ., College Station

- "Theoretical Things for the Humanities," Geoffrey Rockwell, Univ. of Alberta

- "From Artificial Intelligence to Artistic Practices: A New Theoretical Model for the Digital Humanities," Stefano Franchi

- "Object-Oriented Ontology: Escaping the Title of the Book," David Washington, Loyola Univ., New Orleans

Friday, 4 January, 8:30–9:45 a.m., Hampton, Sheraton

Presiding: Alex Mueller, Univ. of Massachusetts, Boston

Speakers: Kathleen Fitzpatrick, MLA; Martin Foys, Drew Univ.; Matthew Kirschenbaum, Univ. of Maryland, College Park; Stephen G. Nichols, Johns Hopkins Univ., MD; Kathleen A. Tonry, Univ. of Connecticut, Storrs; Sarah Werner, Folger Shakespeare Library

In this roundtable, scholars of manuscripts, print, and digital media will discuss how contemporary forms of textuality intersect with, duplicate, extend, or draw on manuscript technologies. Panelists seek to push the discussion beyond traditional notions of supersession or remediation to consider the relevance of past textual practices in our analyses of emergent ones.

Friday, 4 January, 8:30–9:45 a.m., Commonwealth, Sheraton

Presiding: Christine Henseler, Union Coll., NY

- "The Promise of Humanities Practice," Lynn Pasquerella, Mount Holyoke Coll.

- "Making the Humanities ‘Count,’" David Theo Goldberg, Univ. of California, Irvine

- "The National Endowment for the Humanities," Jane Aikin, National Endowment for the Humanities

- "The Humanities in the Digital Age," Christine Henseler

Friday, 4 January, 8:30–9:45 a.m., Beacon D, Sheraton

Presiding: Sophie McCall, Simon Fraser Univ., Burnaby

- "AvantGarde.ca: Toward a Canadian Alienethnic Poetics of the Internet," Sunny Chan, Univ. of British Columbia

- "Intermedial Witnessing in Karen Connelly’s Burmese Lessons," Hannah McGregor, Univ. of Guelph

- "Aboriginal New Media: Alternative Forms of Storytelling," Sarah Henzi, Univ. of Montreal

Friday, 4 January, 10:15–11:30 a.m., Gardner, Sheraton

Presiding: Adeline Koh, Richard Stockton Coll. of New Jersey

Speakers: Moya Bailey, Emory Univ.; Anne Cong-Huyen, Univ. of California, Santa Barbara; Hussein Keshani, Univ. of British Columbia; Maria Velazquez, Univ. of Maryland, College Park

Responding: Alondra Nelson, Columbia Univ.

This panel examines the politics of race, ethnicity, and silence in the digital humanities. How has the digital humanities remained silent on issues of race and ethnicity? How does this silence reinforce unspoken assumptions and doxa? What is the function of racialized silences in digital archival projects?

Friday, 4 January, 12:00 noon–1:15 p.m., Berkeley, Sheraton

Presiding: Susan Brown, Univ. of Guelph

Speakers: Travis Brown, Univ. of Maryland, College Park; Johanna Drucker, Univ. of California, Los Angeles; Eric Rochester, Univ. of Virginia; Geoffrey Rockwell, Univ. of Alberta; Jentery Sayers, Univ. of Victoria; Susan Schreibman, Trinity Coll. Dublin

Working only with set texts limits the use of many digital tools. What most advances literary research: aiming applications at scholarly primitives or at more culturally embedded activities that may resist generalization? Panelists’ reflections on the challenges of interoperability in a methodologically diverse field will include project snapshots evaluating the potential or perils of such aims.

Friday, 4 January, 1:30–3:30 p.m., 210, Hynes

Presiding: Jason C. Rhody, National Endowment for the Humanities

This workshop will highlight recent awards and outline current funding opportunities. In addition to emphasizing grant programs that support individual and collaborative research and education, the workshop will include information on the NEH’s Office of Digital Humanities. A question-and-answer period will follow.

Friday, 4 January, 1:45–3:00 p.m., Back Bay D, Sheraton

Presiding: Richard A. Grusin, Univ. of Wisconsin, Milwaukee

Speakers: Wendy H. Chun, Brown Univ.; Richard A. Grusin; Patrick Jagoda, Univ. of Chicago; Tara McPherson, Univ. of Southern California; Rita Raley, Univ. of California, Santa Barbara

This roundtable explores the impact of digital humanities on research and teaching in higher education and the question of how digital humanities will affect the future of the humanities in general. Speakers will offer models of digital humanities that are not rooted in technocratic rationality or neoliberal economic calculus but that emerge from and inform traditional practices of humanist inquiry.

Friday, 4 January, 1:45–3:00 p.m., Fairfax A, Sheraton

Presiding: Stephen G. Nichols, Johns Hopkins Univ., MD

Speakers: Karen L. Fresco, Univ. of Illinois, Urbana; Albert Lloret, Univ. of Massachusetts, Amherst; Jacques Neefs, Johns Hopkins Univ., MD

Responding: Timothy L. Stinson, North Carolina State Univ.

This panel explores the resistance of editors to explore digital editions. Questions posed: Do scholarly protocols deliberately resist computational methodologies? Or are we still in a liminal period where print predominates for lack of training in the new technology? Does the problem lie with a failure to encourage digital research by younger scholars?

Friday, 4 January, 1:45–3:00 p.m., Jefferson, Sheraton

Presiding: Michael Witmore, Folger Shakespeare Library

- "Touching Apocalypse: Influence and Influenza in the Digital Age," Daniel Allen Shore, Georgetown Univ.

- "The Social Network: Protestant Letter Networks in the Reign of Mary I," Ruth Ahnert, Queen Mary, Univ. of London

- "Credit and Temporal Consciousness in Early Modern English Drama," Mattie Burkert, Univ. of Wisconsin, Madison

Friday, 4 January, 3:30–4:45 p.m., Berkeley, Sheraton

Presiding: James H. Cox, Univ. of Texas, Austin

- "Occom, Archives, and the Digital Humanities," Ivy Schweitzer, Dartmouth Coll.

- "To Look through Red-Colored Glasses: Native Studies and a Revisioning of the Early American Archive," Caroline Wigginton, Rutgers Univ., New Brunswick

- "The Early Native Archive and United States National Identity," Angela Calcaterra, Univ. of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

Friday, 4 January, 3:30–4:45 p.m., Republic Ballroom, Sheraton

Presiding: Michael Bérubé, Penn State Univ., University Park

- "The Mirror and the LAMP," Matthew Kirschenbaum, Univ. of Maryland, College Park

- "Access Demands a Paradigm Shift," Cathy N. Davidson, Duke Univ.

- "Resistance in the Materials," Bethany Nowviskie, Univ. of Virginia

The news that digital humanities are the next big thing must come as a pleasant surprise to people who have been working in the field for decades. Yet only recently has the scholarly community at large realized that developments in new media have implications not only for the form but also for the content of scholarly communication. This session will explore some of those implications—for scholars, for libraries, for journals, and for the idea of intellectual property.

Friday, 4 January, 3:30–4:45 p.m., Hampton, Sheraton

Presiding: Hillary L. Chute, Univ. of Chicago

- "Playful Aesthetics," Mary Flanagan, Dartmouth Coll.

- "Losing the Game: Gamification and the Procedural Aesthetics of Systemic Failure," Patrick Jagoda, Univ. of Chicago

- "Acoustemologies of the Closet: The Wizard, the Troll, and the Fortress," William Cheng, Harvard Univ.

Friday, 4 January, 5:15–6:30 p.m., Fairfax A, Sheraton

Presiding: Domino Renee Perez, Univ. of Texas, Austin

- "’Machete Don’t Text’: Robert Rodriguez’s Media Ecologies," William Orchard, Colby Coll.

- "Convergence Cultura? Reevaluating New Media Scholarship through a Latina/o Literary Blog, La Bloga," Jennifer Lozano, Univ. of Illinois, Urbana

- "César Chávez’s Video Library; or, Farm Workers and the Secret History of New Media," Curtis Frank Márez, Univ. of California, San Diego

Friday, 4 January, 5:15–6:30 p.m., Back Bay D, Sheraton

Presiding: Russell A. Berman, Stanford Univ.

Speakers: Carlos J. Alonso, Columbia Univ.; Lanisa Kitchiner, Howard Univ.; David Laurence, MLA; Bethany Nowviskie, Univ. of Virginia; Elizabeth M. Schwartz, San Joaquin Delta Coll., CA; Sidonie Ann Smith, Univ. of Michigan, Ann Arbor; Kathleen Woodward, Univ. of Washington, Seattle

Doctoral study faces multiple pressures, including profound transformations in higher education and the academic job market, changing conditions for new faculty members, the new media of scholarly communication, and placements in nonfaculty positions. These and other factors question the viability of conventional assumptions regarding doctoral education.

Friday, 4 January, 5:15–6:30 p.m., Berkeley, Sheraton

Presiding: Alan Galey, Univ. of Toronto; Katherine D. Harris, San José State Univ.

- "Echoes at Our Peril: Small Feminist Archives in Big Digital Humanities," Katherine D. Harris

- "The Archipelagic Archive: Caribbean Studies on a Diff Key," Alexander Gil, Univ. of Virginia

- "Universal Design and Disability in the Digital Archive," Karen Bourrier, Univ. of Western Ontario

- "Digital Humanities and the Separation of Access, Ownership, and Reading," Zachary Zimmer, Virginia Polytechnic Inst. and State Univ.

Friday, 4 January, 7:00–8:15 p.m., Back Bay D, Sheraton

Presiding: Peter S. Donaldson, Massachusetts Inst. of Tech.

Global Shakespeares (globalshakespeares.org/) is a participatory multicentric project providing free online access to performances of Shakespeare from many parts of the world. The session features presentations and free lab tours of the MIT HyperStudio.

Saturday, 5 January, 8:30–9:45 a.m., Jefferson, Sheraton

Presiding: James F. English, Univ. of Pennsylvania

- "Enumerating and Visualizing Early English Print," Robin Valenza, Univ. of Wisconsin, Madison

- "The Imaginative Use of Numbers," Ted Underwood, Univ. of Illinois, Urbana

- "Being and Time Management," Mark McGurl, Stanford Univ.

Saturday, 5 January, 8:30–9:45 a.m., Beacon H, Sheraton

Presiding: Michelle Nancy Levy, Simon Fraser Univ., Burnaby

- "The Case against Audiobooks," Matthew Rubery, Univ. of London, Queen Mary Coll.

- "Aural Literacy in a Visual Era: Is Anyone Listening?" Cornelius Collins, Fordham Univ., Bronx

- "Novel Sound Tracks and the Future of Hybridized Reading," Justin St. Clair, Univ. of South Alabama

- "Poetry as MP3: PennSound, Poetry Recording, and the New Digital Archive," Lisa A. Hollenbach, Univ. of Wisconsin, Madison

Saturday, 5 January, 8:30–9:45 a.m., Commonwealth, Sheraton

Presiding: Ryan Cordell, Northeastern Univ.; Katherine Singer, Mount Holyoke Coll.

Speakers: Gert Buelens, Ghent Univ.; Sheila T. Cavanagh, Emory Univ.; Malcolm Alan Compitello, Univ. of Arizona; Gabriel Hankins, Univ. of Virginia; Alexander C. Y. Huang, George Washington Univ.; Kevin Quarmby, Emory Univ.; Lynn Ramey, Vanderbilt Univ.; Matthew Schultz, Vassar Coll.

This digital roundtable aims to give insight into challenges and opportunities for new digital humanists. Instead of presenting polished projects, panelists will share their experiences as developing DH practitioners working through research and pedagogical obstacles. Each participant will present lightning talks and then discuss the projects in more detail at individual tables.

Saturday, 5 January, 8:30–9:45 a.m., Berkeley, Sheraton

Presiding: Julie Rak, Univ. of Alberta

- "Curating Lives: Museums, Archives, Online Sites," Alison Booth, Univ. of Virginia

- "Curating Confession: The Intersection of Communicative Capitalism and Autobiography Online," Anna Poletti, Monash Univ.

- "Digital Dioramas: Curating Life Narratives on the World Wide Web," Laurie McNeill, Univ. of British Columbia

- "Archive of Addiction: Augusten Burroughs’s Dry: In Pictures," Nicole M. Stamant, Agnes Scott Coll.

Saturday, 5 January, 8:30–9:45 a.m., Fairfax A, Sheraton

Presiding: Elissa Marder, Emory Univ.

- "A Sub-sublibrarian for the Digital Archive," Jamie Jones, Univ. of Michigan, Ann Arbor

- "Gangs of New York: Fetishizing the Archive, from Benjamin to Scorsese," Melissa Tuckman, Princeton Univ.

- "Pocket Wireless and the Shape of Media to Come, 1899–1920," Grant Wythoff, Princeton Univ.

Saturday, 5 January, 8:30–9:45 a.m., Public Garden, Sheraton

Presiding: Ana-Maria Medina, Metropolitan State Coll. of Denver

Speakers: Lois Bacon, EBSCO; Marshall J. Brown, Univ. of Washington, Seattle; Stuart Alexander Day, Univ. of Kansas; Judy Luther, Informed Strategies; Dana D. Nelson, Vanderbilt Univ.; Joseph Paul Tabbi, Univ. of Illinois, Chicago; Bonnie Wheeler, Southern Methodist Univ.

Changes are happening to the scholarly journal, a fundamental institution of our professional life. New modes of communication open promising possibilities, even as financial challenges to print media and education make this time difficult. A panel of editors, publishers, and librarians will address these topics, carrying forward a discussion begun at the 2012 Delegate Assembly meeting.

Saturday, 5 January, 10:15–11:30 a.m., Commonwealth, Sheraton

Presiding: Brian Croxall, Emory Univ.

Speakers: Evelyn Baldwin, Univ. of Arkansas, Fayetteville; Mikhail Gershovich, Baruch Coll., City Univ. of New York; Janice McCoy, Univ. of Virginia; Ilknur Oded, Defense Lang. Inst.; Amanda Phillips, Univ. of California, Santa Barbara; Anastasia Salter, Univ. of Baltimore; Elizabeth Swanstrom, Florida Atlantic Univ.

This electronic roundtable presents games not only as objects of study but also as methods for innovative pedagogy. Scholars will present on their use of board games, video games, authoring tools, and more for language acquisition, peer-to-peer relationship building, and exploring social justice. This hands-on, show-and-tell session highlights assignments attendees can implement.

Saturday, 5 January, 10:15–11:30 a.m., Beacon F, Sheraton

Presiding: Paul Werstine, Univ. of Western Ontario

- "Having Your Semantics and Formatting It Too: XML and the NVS," Julia H. Flanders, Brown Univ.

- "Variant Stories: Digital Visualization and the Secret Lives of Shakespeare’s Texts," Alan Galey, Univ. of Toronto

- "Digital Alchemy: Transmuting the Electronic Comedy of Errors," Jon Bath, Univ. of Saskatchewan

Saturday, 5 January, 12:00 noon–1:15 p.m., 301, Hynes

Presiding: Claudia Cabello-Hutt, Univ. of North Carolina, Greensboro; Marcy Ellen Schwartz, Rutgers Univ., New Brunswick

Speakers: Daniel Balderston, Univ. of Pittsburgh; Maria Laura Bocaz, Univ. of Mary Washington; Claudia Cabello-Hutt; Alejandro Herrero-Olaizola, Univ. of Michigan, Ann Arbor; Veronica A. Salles-Reese, Georgetown Univ.; Marcy Ellen Schwartz; Vicky Unruh, Univ. of Kansas

This roundtable will explore renewed interest in Latin American archives—both traditional and digital—and the intellectual, political, and social implications for our research and teaching. Presenters will address how new technologies (digitalized collections, hypertext manuscripts, etc.) facilitate access to research and offer strategies for introducing students to a variety of materials.

Saturday, 5 January, 12:00 noon–1:15 p.m., Liberty C, Sheraton

Presiding: Marta L. Werner, D’Youville Coll.

- "’Every Man His Own Publisher’: Extraillustration and the Dream of the Universal Library," Gabrielle Dean, Johns Hopkins Univ., MD

- "Interactivity and Randomization Processes in Printed and Electronic Experimental Poetry," Jonathan Baillehache, Rutgers Univ., New Brunswick

- "Mirror World, Minus World: Glitching Nabokov’s Pale Fire," Andrew Ferguson, Univ. of Virginia

- "Designed Futures of the Book," Kari M. Kraus, Univ. of Maryland, College Park

Saturday, 5 January, 12:00 noon–1:15 p.m., Commonwealth, Sheraton

Speakers: Sarah J. Arroyo, California State Univ., Long Beach; R. Scot Barnett, Clemson Univ.; Ron C. Brooks, Oklahoma State Univ., Stillwater; Geoffrey V. Carter, Saginaw Valley State Univ.; Anthony Collamati, Clemson Univ.; Jason Helms, Univ. of Kentucky; Alexandra Hidalgo, Purdue Univ., West Lafayette; Robert Leston, New York City Coll. of Tech., City Univ. of New York

This roundtable will present separate, yet unified, digital writings on laptops. Instead of making a diachronic set of presentations, we will make available a synchronic set, in an art e-gallery format, arranged separately on tables as conceptual art installations. The purpose is to demonstrate how digital technologies can reshape our views of presentations and of what is now called writings.

Saturday, 5 January, 1:45–3:00 p.m., Back Bay D, Sheraton

Presiding: Paul Fyfe, Florida State Univ.; Robert H. Kieft, Occidental Coll.

Speakers: Tanya E. Clement, Univ. of Texas, Austin; Rachel Donahue, Univ. of Maryland, College Park; Kari M. Kraus, Univ. of Maryland, College Park; John Merritt Unsworth, Brandeis Univ.; John A. Walsh, Indiana Univ., Bloomington

This roundtable extends current conversations about reforming graduate training to a burgeoning field of disciplinary crossover and professionalization. Participants will introduce innovative training programs and collaborative projects at the intersections of modern language departments, digital humanities, and library schools or iSchools.

Saturday, 5 January, 1:45–3:00 p.m., Hampton, Sheraton

Presiding: Kathi Inman Berens, Univ. of Southern California

- "The Campus as Interface: Screening the University," Elizabeth Mathews Losh, Univ. of California, San Diego

- "Being Distracted in the Digital Age," Jason Farman, Univ. of Maryland, College Park

- "Virtual Classroom Software: A Medium-Specific Analysis," Kathi Inman Berens

- "The Multisensory Classroom," Leeann Hunter, Georgia Inst. of Tech.

Saturday, 5 January, 1:45–3:00 p.m., Public Garden, Sheraton

Presiding: Michael Hancher, Univ. of Minnesota, Twin Cities

- "Dictionaries in Electronic Form: The Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Experience," David Jost, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

- "What We’ve Learned about Dictionary Use Online," Peter Sokolowski, Merriam-Webster

- "Lexicography 2.0: Reimagining Dictionaries and Thesauri for the Digital Age," Ben Zimmer, Visual Thesaurus

Responding: Lisa Berglund, State Univ. of New York, Buffalo State Coll.

Saturday, 5 January, 1:45–3:00 p.m., Liberty A, Sheraton

Presiding: Elizabeth M. Schwartz, San Joaquin Delta Coll., CA

- "Peer Review 2.0: Using Digital Technologies to Transform Student Critiques," Elizabeth Harris McCormick, LaGuardia Community Coll., City Univ. of New York; Lykourgos Vasileiou, LaGuardia Community Coll., City Univ. of New York

- "How I Met Your Argument: Teaching through Television," Lanta Davis, Baylor Univ.

- "Writing Wikipedia as Postmodern Research Assignment," Matthew Parfitt, Boston Univ.

- "Weaning Isn’t Everything: Beyond Postformalism in Composition," Miles McCrimmon, J. Sargeant Reynolds Community Coll., VA

Saturday, 5 January, 3:30–4:45 p.m., Commonwealth, Sheraton

Presiding: Roger Whitson, Emory Univ.

Speakers: David Kim, Univ. of California, Los Angeles; Jennifer Sano-Franchini, Michigan State Univ.; Lee Skallerup Bessette, Morehead State Univ.

Responding: Tara McPherson, Univ. of Southern California

This roundtable addresses how applications and interfaces encode specific cultural assumptions about race and preclude certain groups of people from participating in the digital humanities. Participants present specific digital humanities projects that illustrate the impact of race on access to the programming, cultural, and funding structures in the digital humanities.

Saturday, 5 January, 3:30–4:45 p.m., The Fens, Sheraton

Presiding: Korey Jackson, Univ. of Michigan, Ann Arbor

Speakers: Matt Burton, Univ. of Michigan, Ann Arbor; Korey Jackson; Spencer Keralis, Univ. of North Texas; Jason C. Rhody, National Endowment for the Humanities; Lisa Marie Rhody, Univ. of Maryland, College Park; Michael Ullyot, Univ. of Calgary

This roundtable seeks to query precisely what data can be and do in a humanities context. Charting the migration from individual project to scalable data set, we explore “big data” not simply as a matter of size or number but as a process of granting researchers and educators access to shared information resources.

Saturday, 5 January, 5:15–6:30 p.m., Gardner, Sheraton

Presiding: Jessica Pressman, American Council of Learned Socs.

- "Phonographic Reading Machines," Matthew Rubery, Univ. of London, Queen Mary Coll.

- "Mechanical Mediations of Miniature Text: Reading Microform," Katherine Wilson, Adelphi Univ.

- "Between Human and Machine, a Printed Sheet: The Early History of OCR (Optical Character Recognition)," Mara Mills, New York Univ.

Saturday, 5 January, 5:15–6:30 p.m., Commonwealth, Sheraton

Presiding: Catherine Elizabeth Ingrassia, Virginia Commonwealth Univ.

Speakers: Joshua Eckhardt, Virginia Commonwealth Univ.; Molly Hardy, Saint Bonaventure Univ.; Laura C. Mandell, Texas A&M Univ., College Station; James Raven, Univ. of Essex

Consistent with the theme of open access, this roundtable explores limitations of proprietary digital archives and emergent alternatives. It will provide an interactive, engaged demonstration of 18thConnect; a historian’s perspective; discussion of British Virginia; and scholarly digital editions of seventeenth-century documents.

Saturday, 5 January, 5:15–6:30 p.m., Back Bay B, Sheraton

Presiding: Gabrielle Dean, Johns Hopkins Univ., MD

Speakers: Amanda L. French, George Mason Univ.; George Williams, Univ. of South Carolina, Spartanburg

This "master class" will focus on integrating two digital tools into the classroom to facilitate student-generated projects: Omeka, for the creation of archives and exhibits, and WordPress, for the creation of blogs and Web sites. We will discuss what kinds of assignments work with each tool, how to get started, and how to evaluate assignments. Bring a laptop (not a tablet) for hands-on work.

Sunday, 6 January, 8:30–9:45 a.m., Beacon A, Sheraton

Presiding: Alexander Reid, Univ. at Buffalo, State Univ. of New York

Speakers: Heather Duncan, Univ. at Buffalo, State Univ. of New York; Matthew K. Gold, New York City Coll. of Tech., City Univ. of New York; Eileen Joy, Southern Illinois Univ., Edwardsville; Richard E. Miller, Rutgers Univ., New Brunswick; Daniel Schweitzer, Univ. at Buffalo, State Univ. of New York

Responding: Alexander Reid

As our profession seeks to understand electronic publishing, the emergence of middle-state publishing (e.g., blogs, Twitter) adds another layer of complexity to the issue. The roundtable participants will discuss their use of social media for scholarship and how middle-state publishing alters scholarly work and the ethical and professional concerns that arise.

Sunday, 6 January, 8:30–9:45 a.m., 203, Hynes

Presiding: Yohei Igarashi, Colgate Univ.; Lauren A. Neefe, Stony Brook Univ., State Univ. of New York

Speakers: Miranda Jane Burgess, Univ. of British Columbia; Mary Helen Dupree, Georgetown Univ.; Kevis Goodman, Univ. of California, Berkeley; Yohei Igarashi; Celeste G. Langan, Univ. of California, Berkeley; Maureen Noelle McLane, New York Univ.; Tom Mole, McGill Univ.

A roundtable of scholars discusses and defines “Romantic media studies,” one of the most vibrant approaches to Romantic literature today. Spanning British, German, and transatlantic Romanticisms, the exchange considers Romantic-era media while reflecting on methods of reading for media, mediations, and networks as well as on the relation between Romantic criticism and the digital humanities.

Sunday, 6 January, 8:30–9:45 a.m., Liberty A, Sheraton

Presiding: Victoria E. Szabo, Duke Univ.

- "What Text Mining and Visualizations Have to Do with Feminist Scholarly Inquiries," Tanya E. Clement, Univ. of Texas, Austin

- "Building the Infrastructural Layer: Reading Data Visualization in the Digital Humanities," Dana Solomon, Univ. of California, Santa Barbara

- "What Should We Do with Our Games?" Stephanie Boluk, Vassar Coll.

Responding: Victoria E. Szabo

Sunday, 6 January, 10:15–11:30 a.m., 209, Hynes

Presiding: Rahul Gairola, Univ. of Washington, Seattle

- "Creating Alternate Voices: Exploring South Asian Cyberfeminism," Suchismita Banerjee, Univ. of Wisconsin, Milwaukee

- "Digitizing Pakistani Literary Forms; or, E/Merging the Transcultural," Waseem Anwar, Forman Christian Coll.

- "Reimagining Aesthetic Education: Digital Humanities in the Global South," Rashmi Bhatnagar, Univ. of Pittsburgh

Responding: Amritjit Singh, Ohio Univ., Athens

Sunday, 6 January, 10:15–11:30 a.m., Jefferson, Sheraton

Presiding: John Carlos Rowe, Univ. of Southern California

- "Henry James, Propagandist," Harilaos Stecopoulos, Univ. of Iowa

- "The Art of Associating: Henry James, Network Theorist," Brad Evans, Rutgers Univ., New Brunswick

- "What Would Strether Tweet? James’s Late Style as a New Media Ecology in The Ambassadors," Shawna Ross, Penn State Univ., University Park

- "Henry James and New Media," Ashley Barnes, Univ. of California, Berkeley

Sunday, 6 January, 12:00 noon–1:15 p.m., Hampton, Sheraton

Presiding: Paul Fyfe, Florida State Univ.

Speakers: Katherine E. Gossett, Iowa State Univ.; Erik Hanson, Loyola Univ., Chicago; Matthew Jockers, Univ. of Nebraska, Lincoln; Steven E. Jones, Loyola Univ., Chicago; Bethany Nowviskie, Univ. of Virginia; Sarah Storti, Univ. of Virginia

This roundtable explores the urgent necessity of reforming graduate training in the humanities, particularly in the light of the opportunities afforded by digital platforms, collaborative work, and an expanded mission for graduates. Presenters include graduate students and faculty mentors who are creating the institutional and disciplinary conditions for renovated graduate curricula to succeed.

Sunday, 6 January, 12:00 noon–1:15 p.m., Public Garden, Sheraton

Presiding: Maura Carey Ives, Texas A&M Univ., College Station

- "Analyzing Large Bibliographical Data Sets: A Case Study," David Lee Gants, Florida State Univ.

- "Descriptive Bibliography’s ‘Ideal Copy’ and the Encoding of a Born-Digital Scholarly Edition," Wesley Raabe, Kent State Univ., Kent

- "From the Archive to the Browser: Best Practices and Google Books," Sydney Bufkin, Univ. of Texas, Austin

Sunday, 6 January, 1:45–3:00 p.m., Public Garden, Sheraton

Presiding: Elizabeth Swanstrom, Florida Atlantic Univ.

- "Decoding the Desert: Reading the Landscape through the Transborder Immigrant Tool," Mark C. Marino, Univ. of Southern California

- "Thoreau in Process: Reanimating Thoreau’s Environmental Practice in Digital Space," Kristen Case, Univ. of Maine, Farmington

- "Networks, Narratives, and Nature: Teaching Globally, Thinking Nodally," Melanie J. Doherty, Wesleyan Coll.

Sunday, 6 January, 1:45–3:00 p.m., Liberty A, Sheraton

Presiding: Mark Sample, George Mason Univ.

Speakers: Douglas M. Armato, Univ. of Minnesota Press; Kathleen Fitzpatrick, MLA; Frank Kelleter, Univ. of Göttingen; Kirstyn Leuner, Univ. of Colorado, Boulder; Jason Mittell, Middlebury Coll.; Ted Underwood, Univ. of Illinois, Urbana

This roundtable considers the value and challenges of serial scholarship, that is, research published in serialized form online through a blog, forum, or other public venue. Each of the participants will give a lightning talk about his or her stance toward serial scholarship, while the bulk of the session time will be reserved for open discussion.

Sunday, 6 January, 1:45–3:00 p.m., Back Bay B, Sheraton

Presiding: Sandra K. Baringer, Univ. of California, Riverside

- "A Description of a Situation on the Nontenure Track: Teaching from the Insecure Trenches of a Contingent Online Instructor," Batya Susan Weinbaum, Empire State Coll., State Univ. of New York

- "Hybrid Composition Instruction," Joshua P. Fenton, Univ. of California, Riverside

- "Contract and Policy Language for Adjuncts Teaching Online in the SUNY Community Colleges: A State of the State Report," Cynthia Eaton, Suffolk Community Coll., State Univ. of New York

- "A Strategem for Using Online Courses to Deny Contingent Faculty Members Academic Freedom," Aaron Plasek, Colorado State Univ.

Responding: Maria Shine Stewart, John Carroll Univ.

Sunday, 6 January, 1:45–3:00 p.m., Fairfax A, Sheraton

Presiding: Anaïs Saint-Jude, Stanford Univ.

- "Teaching Modernism Traditionally and Digitally: What We May Learn from New Digital Tutoring Models by Khan Academy and Udacity," Petra Dierkes-Thrun, Stanford Univ.

- "Digital Resources and the Medieval-Literature Classroom," Robin Wharton, Georgia Inst. of Tech.

- "Toward a New Hybrid Pedagogy: Embodiment and Learning in the Classroom 2.0," Pete Rorabaugh, Georgia State Univ.; Jesse Stommel, Marylhurst Univ.