Are you sick of parallax scrolling yet? You know, the way the foreground and background on a web page, iPhone screen, or Super Mario Brothers move at different speeds, giving the illusion of depth? Parallax scrolling is a gimmick. Take it away and not much changes. Your videogame might be a tad less immersive, but come on, how immersive was it in the first place? Turn off parallax scrolling on your phone and your battery life might actually improve. Parallax scrolling is ornamental, a hallmark of what will eventually be known as the Baroque Digital Age.

So it’s with hesitation that I’m attempting to recuperate the word parallax here. In my defense I’m using the word metaphorically, to describe a certain kind of hermeneutical approach to textual material.

Here it is: parallax reading, an interpretive maneuver that keeps both close and distant reading in focus at the same time.

If you’re just tuning in to the digital humanities, there’s a pretty much bogus IMHO tension between close and distant reading. Close reading is that thing we were all taught to do in high school English, paying attention to individual words and the subtle nuances of a text. Distant reading zooms out to look at a text—or even better, a massive body of texts—from a distance. In Franco Moretti’s memorable words, distance is “not an obstacle, but a specific form of knowledge: fewer elements, hence a sharper sense of their overall interconnection. Shapes, relations, structures. Patterns.”1

Cool, patterns.

“Parallax reading” is a fancy way of saying why not combine close and distant reading. And to be clear, no one is saying you can’t. Again, it’s a bogus tension, a straw man. I’m not proposing anything new here. I’m just giving it a name. And in a bit, a demo.

A parallax reading is the opposite of the “lenticular logic” that, as Tara McPherson explains, separates the two images on a 3D postcard, making it impossible to see them simultaneously. Whereas lenticular vision flips between two distinct representations, parallax reading holds multiple distances in view at once. Like its visual counterpart, parallax reading conveys a sense of depth. Unlike parallax scrolling, though, this is depth that actually matters, a depth that complicates our understanding of texts.

What would a parallax reading look like?

As a case study let’s look at Theodore Roethke’s poem “My Papa’s Waltz.” Written from the perspective of a young boy, the sixteen line poem captures a possibly tender, possibly terrifying moment, as his boozy father mock waltzes him “off to bed.” The whiskey on his father’s breath makes the boy “dizzy.” His mother looks on, barely tolerating the nonsense. The boy is so small he only comes up to his father’s waist; his dad’s belt buckle scrapes his ear with “every step.” As the boy goes to bed “still clinging” to his father’s shirt it’s not clear whether he’s clinging out of fear or love, or maybe both.

“My Papa’s Waltz” was published in 1942 and by the mid-50s was already widely anthologized. It’s a great poem, and I love teaching it. And so do other people. There’s a lot going on under its deceptively simple surface. In The Literature Workshop (a book every teacher of literature should study), Sheridan Blau uses “My Papa’s Waltz” to confront two questions that often arise in literature classes: where does meaning come from, and how the hell do we know which meaning is the right one?

Blau observes that for twenty years or so he taught “My Papa’s Waltz” and students overwhelmingly read it as nostalgic, the fond recollection of a grown man of his gruff but loving father. Then, sometime in mid-80s, Blau’s students began to read the poem more darkly, a vivid childhood memory about abuse and a dysfunctional family.

What happened? How can the poem mean both things? At this point you might be thinking, ah, so a parallax reading is simply holding two opposing meanings of the poem in place at the same time. This is what sophisticated readers and writers do all the time. For example, Sherman Alexie describes “My Papa’s Waltz” as

A love poem about, as Alexie says later on, “the unpredictability of the alcoholic father.” Two seemingly incompatible interpretations—incompatible, that is, to a naive reader. Is this what I mean by parallax reading? Are two competing perspectives we keep in simultaneous focus what parallax reading is all about?

No!

Embracing ambivalent or contradictory interpretations is nothing new. Hopefully, literary scholars practice this—and teach it—all the time. (If anything, we celebrate ambiguity a little too much, when what the world needs now is some rock solid truth, right?) Anyway, a parallax reading is not about the interpretative outcomes, it’s about the methodological process. It’s about simultaneously negotiating close and distant readings.

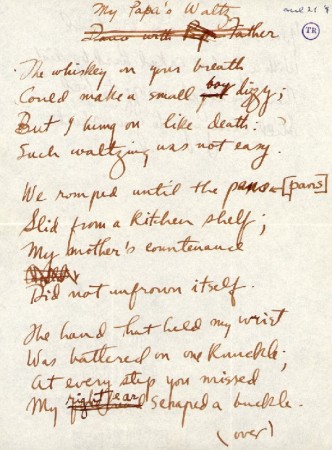

Think about “My Papa’s Waltz” from a close reading perspective (the foreground of the parallax). An array of historical evidence might suggest which interpretation of his poem Roethke himself preferred. For example, we could look at drafts of the poem, which indicate several significant revisions. In one draft, the small boy is a girl and the “right ear” scraping a buckle is the less particular “forehead.”

Changing the gender of the speaker recasts the the father-son relationship as a father-daughter relationship. We might be less likely to read biographical details of Roethke’s own life into the poem: his father ran a gigantic greenhouse, worked with his hands, and died of cancer when Roethke was 14-years-old. Would any of that matter if the speaker is a girl? Would any of it matter either way?

We could also listen to Roethke’s own delivery of the poem. At least two recordings are available online. One features Roethke reading in a sing-song voice that bears no trace of fear or resentment. Another Roethke reading is somber, the accent on the words “you” in the third stanza and “beat” in the fourth stanza possibly ominous, possibly not.

Or—and this is novel—we could actually read the poem. Here’s what I did last time I taught “My Papa’s Waltz.” (I wasn’t teaching Roethke’s poem per se, I was teaching Blau’s book, in a grad class on the pedagogy of teaching literature.) I’m a fan of reading aloud in class, and that’s what we did. As we read, I asked students to point—literally, point with their index finger—to the words that were most freighted with abuse. “Scraped” and “beat” drew some attention from the students, but invariably the word with the strongest connotation of abuse for the students was “battered.” Roethke uses “battered” to describe the father’s hand—it was “battered on one knuckle”—but students couldn’t help displacing the word onto the small boy himself. It’s as if by metonymical extension the boy too was battered and bruised.

With “battered” coming into focus during our close reading as a key marker of abuse, let’s shift to a distant reading of “My Papa’s Waltz”—the background of the parallax. But how can we zoom out from a single poem? From a distance, what’s there to look at? If one poem is a drop of water, what’s the ocean of words that contains it?

One possible ocean is Google Books. Google ngrams offers a snazzy interface for tracking word frequency over time, based on Google Books’ dataset, a staggering 155 billion words in American English. Since my students found “battered” to be the center of traumatic gravity of “My Papa’s Waltz” I plugged that word into Google ngrams:

[iframe name=”ngram_chart” src=”https://books.google.com/ngrams/interactive_chart?content=battered&year_start=1800&year_end=2000&corpus=15&smoothing=3&share=&direct_url=t1%3B%2Cbattered%3B%2Cc0″ width=800 height=300 marginwidth=0 marginheight=0 hspace=0 vspace=0 frameborder=0 scrolling=no>]Which is honestly not that useful. Ngrams can show the rise and fall of certain terms, but they’re inadequate for more nuanced inquires. There are at least three reasons the Google ngram viewer fails here: (1) Google ngrams limits searches by collocates, that is, immediately preceding and succeeding words; (2) Google ngrams can’t search for parts of speech; and most significantly (3) Google ngrams provides no context for the words—no sentence context, no source context, nothing.

This is where the Corpus of Historical American English (COHA) comes in. COHA is a dataset of 400 million words from 1810 through 2009. Established by Mark Davies at Brigham Young University, COHA includes fiction (including texts from Project Gutenberg, scanned books, and scanned movie scripts) and nonfiction (including scanned newspapers and magazines). COHA is a smaller dataset than Google Books, but it holds several critical advantages over Google Books. You can search for phrases that aren’t necessarily collocated right next to each other. You can specify what part of speech you want to search for. That’s really important if you’re looking for a word like, oh, I don’t know, “trump,” which can be a verb, noun, proper noun, and a few other things. Finally, COHA provides context for its searches.

For the time period of the 1950s, when “My Papa’s Waltz” had already been widely anthologized, COHA includes nearly 12 million words from fiction sources, 5.7 millions words from popular magazines, 3.5 million words from newspapers, and just over 3 million words from nonfiction books. That’s a total of 24 million words from the 1950s, which gives us a representative view of how language was being used across a number of domains at the time. This is the ocean of words that surrounds “My Papa’s Waltz.”

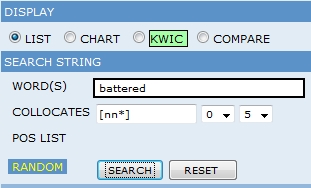

Let’s check out “battered” in COHA, to see how the word was being used during Roethke’s time and afterward.

Here are our search parameters, which tell COHA to find any occurrence of “battered” followed within five words by a noun (that’s the [nn*] in the Collocates box). This search acknowledges that the frequency of “battered” isn’t as important as its context.

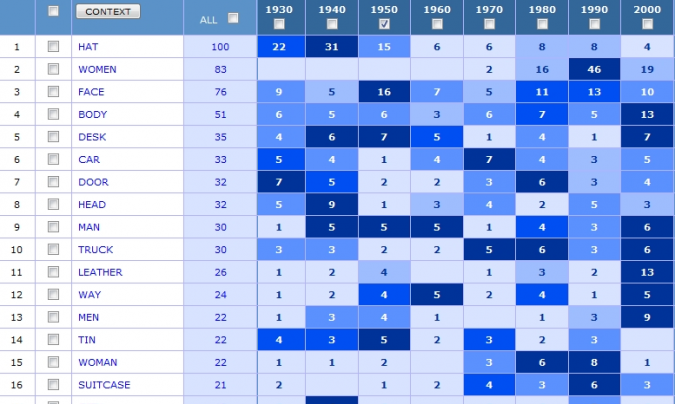

The results are immediately striking. We have the kind of patterns Moretti seeks in distant reading.

The second most common noun following “battered” is women, as in “battered women.” This frequency would appear to support the idea that “battered” in “My Papa’s Waltz” is an indicator of abuse. At the very least, its appearance is ominous.

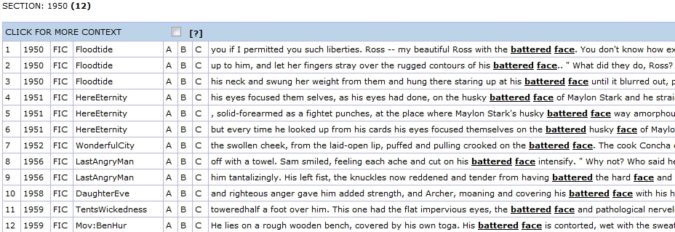

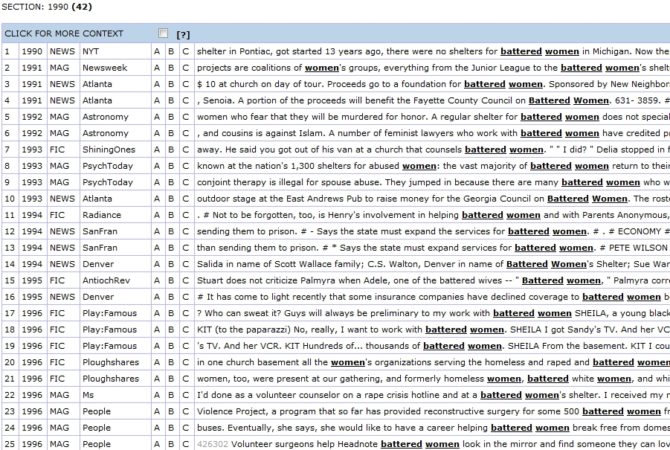

Yet dig deeper and notice that the variants of “battered…women” do not become prevalent until 1980 (with 16 occurrences) and peak in the 1990s with 46 occurrences. Prior to 1970, “battered” is rarely used in the context of physical abuse against women.

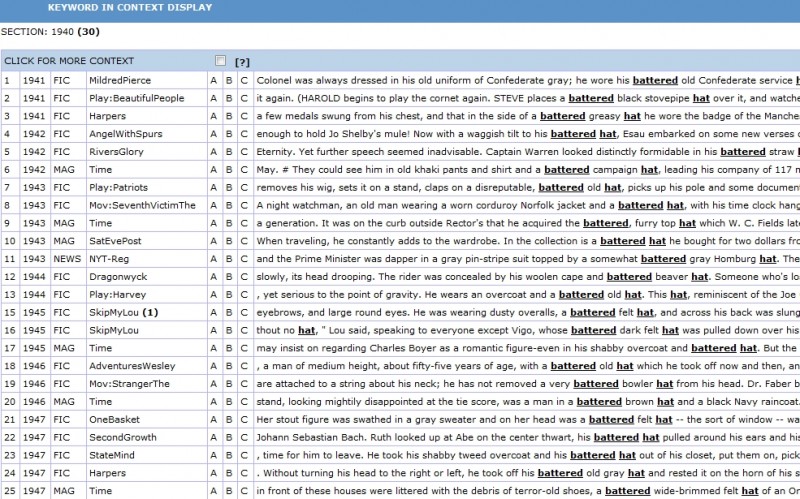

So what does “battered” typically describe when Roethke published the poem in 1942 and in the years immediately afterward? In the 1940s the most common collocate was “hat”: “a battered black stovepipe hat,” “a battered greasy hat,” “his battered hat,” “a disreputable, battered hat”—all uses that suggest a knocked-about, down-on-one’s-luck man. Here’s the KWIC (Keyword In Context) display for “battered…hat” in the 1950s:

And look at the third most common noun associated with “battered.” It’s “face,” peaking in the 1950s. This detail might appear to support the negative interpretation of “My Papa’s Waltz.” But again, look at the keyword in context.

The battered face here is predominantly a male face, battered by wind, hard living, and frequently, war. This is likely the kind of “battered” Roethke had in mind when he described the rough hands of the boy’s father in the poem.

Contrast this with how battered appears in the 1990s, when it is associated most frequently with “women”:

Here we find “battered” being used the way today’s students would understand the word, associated with the physical abuse of women by men. (Grammar fun: “battered” is technically a participial adjective. It’s an adjective that started out as a participial phrase, but was shortened. Like “there were no shelters for battered women in Michigan” (the first example from the KWIC above) really means “there were no shelters for women who were battered by men in Michigan.” The agent—the men inflicting the battering—drops out of the sentence and we’re left with inexplicably battered women, and no party to take responsibility. Basically it’s passive voice in disguise, a way for abusive men to get off scott-free, linguistically speaking.)

So, a theory: “battered” is what I would call a cusp word—a word teetering on the cusp between two opposing meanings. On one side, the word suggests strength and resilience. It’s gendered masculine in this context. On the other side it suggests helplessness and victimization. It’s gendered female in this case. In other words, once associated with men at the mercy of the elements or men who have endured hardship, “battered” is now associated with women who have suffered—though this part is kept hidden by the participial adjective—at the hands of men.

We still occasionally encounter the older meaning of the word. A line from Leonard Cohen’s “Democracy” (1992) comes to mind:

From the brave, the bold, the battered heart of Chevrolet

Democracy is coming to the USA

Here “the battered heart of Chevrolet” is a stand-in for Rust Belt America, the industrial wasteland that left blue collar working men out of work. Or “stiffed,” as Susan Faludi put it in her eponymous diagnosis of 20th century masculinity.2 I’m no sociologist, but it’s not difficult to imagine that “the battered heart of Chevrolet” contributed to a sense of helplessness in men that found expression in violence against women. Emasculated men beating their way to empowerment. Thus battered souls lead to battered bodies.

We can’t know for certain, of course, but it makes sense that Roethke’s description of the father’s hands as “battered” is a kind of tribute to the man. An acknowledgment of hard work and sacrifice. Roethke’s vocabulary was shaped by the Great Depression and World Wars, an era of stoic endurance (even if that stoicism was a myth). People reading the poem today, however, see in “battered” the ugly side of human nature. Desperation, rage, brutality.

In his explanation of his students’ changing interpretation of “My Papa’s Waltz”: Blau suggests that “a change in the culture made a particular reading available that had not been culturally available before.”3 Blau’s exactly right. That shift in meaning began in the 1980s, concomitant with growing social awareness of domestic abuse. What Blau doesn’t say—because the tools weren’t culturally available to him at the time—is that thanks to a distant reading, we can find evidence of that shift within a single word of Roethke’s poem.

What’s important for a parallax reading is that neither foreground nor background disappear entirely. In fact, they only make sense when considered together. That’s where the sense of depth comes from. Armed with knowledge gleaned from distant reading we can go back to the poem and read it again. And maybe, recursively, find other words to track across time, or to contextualize historically. But we always return to the poem.

Will a parallax reading definitively answer the question, what’s “My Papa’s Waltz” about? No. The beauty of literature and language more generally is its ambiguity (argh, though again, maybe we tolerate a little too much ambiguity). But, I have discovered evidence that complicates our interpretation of the poem. At the very least, it should shock us out of our presentist approach to language, assuming the way we use words is the way those words have always been used. And even more importantly, it’s not that I have found answers about the poem. It’s that I found a new way to ask questions.

Notes

Moretti, Franco. “Graphs, Maps, Trees 2: Abstract Models for Literary History.” New Left Review, vol. 26, no. March-April, 2004, p. 94.↩

Faludi, Susan. Stiffed: The Betrayal of the American Man. Harper Perennial, 1999.↩

Blau, Sheridan. The Literature Workshop: Teaching Texts and Their Readers. Heinemann, 2003, p. 73.↩